- Home

- Judith Fertig

The Cake Therapist Page 3

The Cake Therapist Read online

Page 3

Rounding the corner, three men in bowler hats and stiff-collared shirts strode toward the young people.

“Great morning for our little trip up to Lockton, Miss Parsons and Mr. Nash.” The oldest-looking man nodded to them, tipping his hat to Ethel. He looked like a port-drinking gentleman, she assessed quickly, and she envisioned a well-run household with a potted palm in the front bay window of the parlor and maids in black dresses and white pinafores.

“George Taylor, at your service.”

She extended her gloved hand to shake his, but he gallantly raised her hand to his lips and gave it a courtly peck. Ethel blushed as she withdrew her hand, then blushed at the thought that she had blushed to begin with.

Mr. Taylor smiled benignly at her, eyes twinkling, then informed the group, “We’ve asked the captain’s wife to come along and make us coffee. She’s also frying her famous crullers.” The Simms & Taylor men’s eyes widened in delight. Taylor turned back to Ethel. “You won’t be able to wear your pretty gloves and eat one of Mrs. Skillman’s crullers; I can vouch for that.” She blushed yet again as all three men chuckled.

She stole a look at Ben, and he was smiling, too, not annoyed, so all was well.

The Simms & Taylor men led the way onto the short deck of the squat canal boat, then down the three steps into the hold, where a large enameled coffeepot sat on a small cast-iron stove. Mrs. Skillman, a rawboned woman in a long dark dress covered by a striped pinafore-style apron, smiled uncertainly. The little, low-ceilinged room smelled of coffee and frying, the welcome aroma of breakfast.

When everyone was seated, Captain Skillman roared the motor into life. It then quieted to a steady hum, and the boat slowly chugged upstream.

Taylor gave the two designers a bit of the company history, from their beginnings in the 1840s making special-order carriage upholstery in Queen City, to their expanded mill and factory fifteen miles north up the canal in Lockton. It was the modern Lockton mill that the boating party was now on the way to visit.

Ethel took out her sketches and arranged them on the gateleg table in the center of the small room.

Mrs. Skillman served the coffee in cups and saucers. She gave each person a starched and ironed napkin, then passed a basket of cinnamon sugar–dusted crullers, still warm from the lard in which she’d fried them.

For the next two hours, they sat around the table talking rosebuds, filigree, vines, and scrolls versus more classical acanthus leaves and urns. Ethel had brought several sepia wedding photos of working-class couples, borrowed from a photographer friend.

At first, the Simms & Taylor men saw only the unsmiling couples, looking straight into the camera, rigidly posed in their best clothing. But, as Ethel explained, this might be the only photo they would ever have taken of themselves, and they wanted it to be respectful, dignified. There was the requisite formal chair, with either the bride or the groom seated and the other standing. There was a suggestion of a Persian carpet on the floor. A bouquet of flowers. The bride’s hand posed to show the ring, no matter how modest.

“They want better than what they’ve had,” Ethel commented. “If you look closer at the dresses, you’ll notice lace, satiny stripes, dressmaker details like bows and those tiny rosebuds sewn from ribbon.” She pointed to several photos and the rosebuds just visible on the trim of a sleeve or a bodice. “These women may live in tenements, but they dream of gardens.”

Ben sat quietly. Ethel had prepared well and the men seemed to respect that. Ben’s job was matching the aesthetic to the technical—could these designs be woven, with an eye for the bottom line, on a factory loom? Would the design work for a mattress cover?

As Mrs. Skillman poured another round of coffee, Ethel boldly asked her, “Which design do you like best, ma’am?”

The men looked at one another. Why ask this poor woman?

“Oh, I’m sure I couldn’t say,” the captain’s wife murmured as she noticed their puzzled frowns, backing away from the table.

And then it dawned on them. She was a working-class woman—their customer.

George Taylor motioned her back. “I’m going to give you twenty-five dollars.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out bills secured with an engraved money clip.

Mrs. Skillman looked uneasy. “You’re very generous, to be sure, sir.” It was more than the Skillmans usually made in a week.

“I’m paying you for your opinion, Mrs. Skillman,” George explained. “If you were going to buy something for your home with that money,” Taylor said, talking with his hands, “maybe it’s wallpaper, curtains, a divan—”

“Or a mattress,” one of the men joked.

“In one of these patterns,” Taylor continued, “which one would you buy? It’s important that we know. Very important. You would be helping us quite a bit.”

“All right, sir, if you put it that way.”

“Now, have a look at these,” he said, motioning her to look over the drawings. Mrs. Skillman considered each one in her methodical way. She wiped her hands on her apron, then pointed with a blunt, work-roughened finger to the design with the most flowers—climbing roses on classical pillars against a background of scrollwork.

The men looked at one another, at Ethel, and they all nodded. Taylor gave the money to Mrs. Skillman, who didn’t know whether to bow or curtsy, and so did a bit of each before nervously stuffing the bills in her apron pocket.

“Ben?” Taylor asked.

“The looms can handle it,” he said. “Might take a week or so to set the pattern, but the design should work.”

Now that one of the designs was settled, they looked over the other sketches to choose two more.

Mrs. Skillman was gathering up the last of the coffee cups when a sharp crack of thunder cleaved through the conversation. They all turned to look out the small eyebrow windows and saw an ominously darkened sky.

The boat seemed to shudder to a stop before the lock, which could gradually take a canal boat from a lower to a higher level of water before proceeding north to Lake Erie. But the Aurora would simply turn around and make its halfhearted trip back down to Plum Street.

Captain Skillman jumped down from the captain’s berth onto the old towpath while his boy tied up the boat with a thick loop of rope.

“Let’s finish this up at the factory,” said Taylor, rising from the table.

They gathered up their belongings in a rush. Ethel’s gloves fell on the floor, but she didn’t notice.

This time, the captain handed Ethel up to the shelter of a large black umbrella, held by the factory foreman. She had just enough time to take a quick glance across the canal. The chimneys from the paper mill and the asphalt-shingle factory sent smoke up into the heavy air.

Rain began to fall like dirty net curtains.

The foreman walked to her left, nearest the canal, gripping her elbow. They hurried to the mattress factory, which was looming like a fortress.

When the foreman stopped suddenly on the towpath to navigate around a murky puddle, Ethel peered up again at the coal-darkened brick building. The factory’s massive five stories rose like Sleeping Beauty’s castle under the enchantment of a dark fairy, she mused. It was surrounded, not by a thorny thicket as in the fairy tale, but by a darker spell that Ethel sensed, but could not see: cotton dust, coal smoke, and tiny filaments of asbestos.

Close to the lock, the wind spun around, pelting them from the other side with cold rain. Her wet hands quickly reddened and numbed.

Ethel hoped her petticoat and skirt weren’t ruined. But she couldn’t ruck up her skirt and hold on to the foreman and her sketches all at the same time. As she tucked her portfolio higher up under her right arm, Ethel didn’t feel the ring loosen, slip from her fingers, and disappear into the mud.

2

“Everything looks so beautiful,” Mrs. Schumacher said, sitting demurely on the settee in my

front parlor.

I hoped so. A lot was riding on this wedding cake tasting. The Schumachers were a Carriage Hill society family. If they booked their wedding cake with me, word-of-mouth alone would be just the start that Rainbow Cake needed.

The mother of the bride looked like a sixtysomething, well-to-do matron in her navy pantsuit, sensible shoes, and good jewelry, with those telltale vertical lines right above her upper lip. Her hair was expensively cut in a classic bob. Her face was reddened, with tiny capillaries visible on her nose. Not from drink, I decided, but from being outdoors. Like other Carriage Hill residents, the Schumachers probably had a stable on their property and rode their horses on the trails that meandered for miles in the wooded, hilly terrain.

Ellen Schumacher, the bride-to-be whose streaked blond hair was pulled back in a charmingly loose knot, wore a fitted white shirt with a pale lavender cashmere sweater tied across her shoulders. Well-tailored charcoal gray trousers, good leather boots. Pearl earrings that caught the light. Understated makeup on a flawless complexion. Intelligent gray-blue eyes. Early thirties. She seemed sure of herself. Excited, but also composed.

They could certainly afford my services or they wouldn’t be here.

My wedding and couture cakes were at the top tier, price-wise. Quality counted, but so did showmanship and ambience. Customers had to be convinced of that.

So, I took them out of the bakery and next door to my house, the front porch doorway now flanked by black iron urns filled with fresh evergreen boughs for winter. And, of course, I also had the dressed-up concrete goose that Roshonda had given me, just to keep things lighthearted. That wedding planning can get a little tense was an understatement, I was finding out.

My front parlor was simple yet sophisticated, with plaster walls painted a soft French gray, the woodwork a subtle ivory, and a few landscape paintings that I had brought with me from my Brooklyn brownstone. Here we could close the painted shutters halfway to block off the sights and sounds of Benson Street. I wanted my potential clients to feel that they were in another world.

A gas fire in the white marble Victorian hearth warmed the room against the chilly afternoon and cast the bookcases into shadow. The round table with its heavy cloth in nubby French linen was set with a coffee service and a French press coffeepot. A wooden tray shaped like an artist’s palette—one I had specially made—held small clear cups of pastel-colored fillings and frostings. Miniature cupcakes in their paper frills filled a tiered stand.

Ellen sat next to her mother and reached across the table to take the thin china coffee cup that I offered. An antique ring was still a little loose on her finger.

“May I see your engagement ring?” I asked, mentally crossing off one of the questions during a wedding cake tasting, although in this case, I truly did want to see it up close.

With a shy smile, she let me take her French-manicured hand to have a good look. Old-fashioned. Yellow gold, fine craftsmanship, the patina of age. Tiny golden leaves inset with pearls held the oval sapphire. It was simply stunning.

“That is the most beautiful ring I’ve ever seen,” I said, and meant it.

“It’s been in my fiancé’s family for quite some time,” she replied. “Sam and I just got engaged.”

We all sipped the coffee, and I took a moment to clear my mind so I could focus on this bride, this family. I closed my eyes for a second or two and let the flavor come to me.

What I got was a hint of spice.

When I lived in New York and went to Chinatown, I learned that these flavors and their meanings were actually a foundation of ancient Chinese medicine.

Salty translated to fear and the frantic energy that tries to compensate for or hide it.

Sweet was the first flavor we recognized from our mother’s milk, and to which we turned when we were worried and unsure or depressed.

Sour usually meant anger and frustration.

Bitter signified matters of the heart, from simply feeling unloved to the almost overwhelming loss of a great love. Most spices, along with coffee and chocolate, had some bitterness in their flavor profile. Even sugar, when it cooked too long, turned bitter. But to me, spice was for grief, because it lingered longest.

The more intense the flavor, the more intense the feeling, I also knew. This taste of spice I was getting seemed a little dulled, but still apparent. Now I knew how to proceed.

I broached the subject gently. “Before we get started, I’d like to know a little more about your family.”

Ellen looked at her mother, then answered. “I’m very lucky to have a great family. There’s my mom,” she said, and she smiled across the table. “She’s helping me plan everything. My brother, Ted, who is also a good friend of Sam’s, will be best man. My father passed away when I was in law school, so my uncle will walk me down the aisle. My cousin,” she continued, but I was not really listening.

So there it was. The loss of her father softened by the passing of time but brought back by this family milestone.

A little girl sits high up on her horse, gripping the reins tightly in pudgy little hands. The strap on her velveteen riding helmet fits firmly under her chin. A tall, good-looking man with dark, wavy hair leads the horse by the bridle, but lets her think she’s doing it all herself. He gives her a tender, wry smile. “Keep your heels down in the stirrups, Ellie. And loosen that stranglehold you have on poor Snowflake. She’s never going to let you ride her again.” Ellie angles the heels of her short paddock boots downward, loosens her grip on the reins, and finds that she sits better on her mount. The delight of her discovery shows on her face, and her dad beams. “That’s my girl.”

“. . . and my other cousin, Alicia, will be taking care of the gift table.”

I smiled and nodded. “You’ve obviously got everything well planned. Now, for the cake!” I said brightly, getting down to business. “Your wedding cake should reflect not only the look of your wedding, but the flavor of your partnership, your unique blending of two lives.”

Ellen and her mother were both nodding, taking in what I was saying.

“We’re tasting today so we can create a signature cake for Ellen and Sam. This cake will be your love story translated into cake, filling, and frosting. So we want to make sure we get it right.”

“Just like a perfumer who would create the perfect scent for you with top, middle, and base notes, we’ll build the perfect cake that really captures the two of you.”

“But,” Mrs. Schumacher interrupted, “shouldn’t we be choosing a cake that our guests will like? What if Ellen wants banana or Sam’s favorite flavor is chocolate? I know her grandmother hates banana, and a chocolate wedding cake . . . I just don’t think . . .”

Ellen smiled. “Don’t worry. I won’t choose banana, Mom. And Sam doesn’t like chocolate all that much.”

I poured more coffee for them both. “We’re talking about subtle flavor here, Mrs. Schumacher,” I reassured her. “We can even make an all white cake with white buttercream frosting taste different for each bride and groom.” She looked back at me, perplexed.

“I thought all white cake tasted like white cake.”

“Not if we add subtle flavorings. Let’s just begin tasting, then, and you’ll know what I mean.”

I took two of the unfrosted, miniature cupcakes and placed them on a small tray in front of me. “Now, this is our pound cake that has been infused with vanilla bean. Let’s try this first with a blood-orange mousse. It’s made with one of our French syrups added to the mousse. This also has a slight hint of spice—China cassia cinnamon and star anise. I find that the spice gives a little lift, but you hardly know it’s there.” I’d used a palette knife to smooth the filling on top of each cupcake.

“I love the color,” said Ellen. “That pale coral would be beautiful with the cobalt blue and ivory—they’re our wedding colors.”

“Yes, that would be

lovely,” I continued. “Now, let’s also smooth on the classic buttercream and see if you like the combination.”

Ellen and her mother took one bite, then another. They looked at each other and smiled. I knew that the cake made them think of the husband and father not with them anymore. They remembered him smiling, happy, young, as I had seen him, too.

Ellen looked away, and I felt her sadness for a member of Sam’s family who also had passed. I wouldn’t ask who it was, as I didn’t really need to know. The subtle spice flavor would recognize Sam’s family’s yearning to see that loved one again, too, then feed it.

We sampled other cakes—the white cake that tasted faintly of almond, the chocolate with its hint of coffee. And the other mousses—the raspberry with a drop of rose syrup to bring out its fruitiness. Lemon, almond, lavender, pistachio—but I knew this was it.

My laptop with its PowerPoint presentation of cake designs was ready to cast its magic on the smooth wall between the two long front windows. Seeing the cake bigger rather than on the small laptop screen always made it seem more real.

After the tasting, we chose a cake design. Ellen had brought photos of her wedding dress and bridesmaids’ dresses. The Schumachers also wanted sugar cookies decorated to look like the bridesmaids’ dresses and wedding cakes—wrapped in cellophane and tied with ribbon in the couple’s wedding colors—for the bridesmaids’ luncheon and as wedding favors for guests.

After an hour, we went over the contract. I sensed a slight hesitation from Mrs. Schumacher. That was understandable. Rainbow Cake was new, and this was the first wedding cake the bakery would craft. I emphasized my experience with wedding cake artist Sylvia Weinstock in Manhattan, how I had assisted with many cakes for many notable weddings, cakes Mrs. Schumacher had seen on my laptop and tasted in my parlor. She finally gave me her credit card for the deposit. In my office on the second floor, I made copies of everything for them and put all their materials in Rainbow Cake’s signature robin’s-egg-blue-and-chocolate-brown folder.

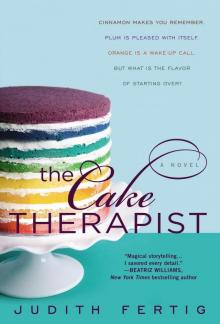

The Cake Therapist

The Cake Therapist