- Home

- Judith Fertig

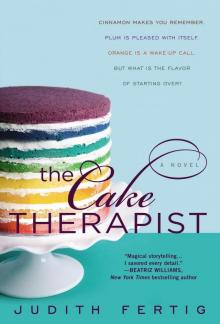

The Cake Therapist

The Cake Therapist Read online

“A delicious treat for readers . . . Like a master chef, Judith Fertig takes the tale of a gifted baker starting all over in her old Midwestern hometown and layers it together with an intriguing mystery buried deep in the community’s Depression-era past.”

—Beatriz Williams, New York Times bestselling author of Tiny Little Thing

“In a small town where secrets run deep and over generations, Fertig shows friendship, family, and food can bring people together and heal old wounds. A novel that is a true treat for the senses.”

—Jill Shalvis, New York Times bestselling author of Still the One

“This delicious debut will leave your mouth watering and your eyes moist . . . A heartwarming story of community, love, and food so delectable you want it to leap off the page into your mouth.”

—Linda Rodriguez, award-winning poet and author of Every Hidden Fear

“A dash of complex romance stirs up a cast of characters linked through time by a precious bauble in a delicious setting. This sweet charmer of a story made me hungry for more.”

—Jeanne Ambrose, award-winning writer, cookbook author, and editor of Taste of Home magazine

“The Cake Therapist is charming, captivating, and crave-worthy. Not only do I want to meet (and be friends!) with Neely after reading her story; I want to taste every one of her deliciously therapeutic treats. How I wish I knew what flavor she would choose for me!”

—Denise Mickelsen, cooking, baking, and gardening acquisitions editor at Craftsy

“Fertig expertly weaves a redemptive tale of then and now, of sweetness and pain, all while slowly unraveling a mystery that had me flipping pages faster and faster until its surprising ending.”

—David Leite, publisher of Leite’s Culinaria

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

This book is an original publication of Penguin Random House LLC.

Copyright © 2015 by Judith Fertig.

“Readers Guide” copyright © 2015 by Penguin Random House LLC.

Excerpt from The Memory of Lemon by Judith Fertig copyright © 2015 by Judith Fertig.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

BERKLEY® and the “B” design are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

For more information, visit penguin.com.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-18041-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fertig, Judith M.

The cake therapist / Judith Fertig.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-425-27732-4 (paperback)

1. Women—Fiction. 2. Bakers—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3606.E78C36 2015

813'.6—dc23

2015002608

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Berkley trade paperback edition / June 2015

Cover photo by Edward Djendrono / Getty Images.

Cover design by Rita Frangie.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For my family,

who make life sweet

and help me practice real-life cake therapy

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Where to start? At the beginning. First of all, to my parents, Jean and Jack Merkle, whose love and support have been constant and who raised me in a very interesting place, as it turns out. Many thanks to my sister, Julie Fox, and her family for uncorking the champagne. Merci beaucoup to Le Cordon Bleu in London and Ecole de Cuisine La Varenne in Paris for my culinary education. You can’t write without a life, and I’m so happy to have daughter Sarah, son Nick, daughter-in-law Jessica, soon-to-be son-in-law Eric, and little Anya Sofia in mine.

The Cake Therapist wouldn’t be here if not for my friend and BBQ cookbook coauthor Karen Adler, who listened to me blab about this idea for years as we drove to teach classes at cooking schools around the country. A dose of cake therapy to Deborah Shouse and Mary Lane Kamberg, who read a very early chapter in which nothing much happened. A tip of the chef’s toque to Kelly Dwyer and “The Plotters” at the Iowa Summer Writing Festival for getting the plot going. Thanks to the amazing Vivien Jennings of Rainy Day Books and the judges at the Kansas City Pitchapalooza, who put me in touch with Arielle Eckstut and her great advice. I’m indebted to the Writers’ Colony at Dairy Hollow for the deep time in which to write the first draft. Warm thanks to Dee Barwick, Mary Ann Duckers, and my cookbook agent, Lisa Ekus, who read an early draft.

Many, many thanks to Linda Rodriguez, who brought me into the Kansas City Novel Writers Group, which also includes Jacqueline Guidry, Robin Silverman, and Deborah Shouse. I’m grateful to my delightful cookbook editor, Kristen Wiewora at Running Press, who put her stamp of approval on the title over ice cream in Philadelphia.

Once The Cake Therapist was ready to go, I had the great fortune to sign with the talented Stefanie Lieberman of Janklow & Nesbit. She led me to editor Kate Seaver, of the keen eye, warm sensibility, great sense of humor (and superb taste)—plus everyone at the Berkley Publishing Group of Penguin Random House. It truly does take a village.

And all of this has led me to you, dear reader. Enjoy! Let’s stay in touch at judithfertig.com.

CONTENTS

Praise for The Cake Therapist

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Readers Guide

A preview of The Memory of Lemon

Prologue

DECEMBER

The windows at Macy’s were dressed in the usual high-wattage holiday fanfare, and the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Plaza twinkled as valiantly as ever. But for me, December had been gray and blah, like suffering through the end of a cold when you couldn’t taste anything.

Instead of hurrying down Fifth Avenue with shopping bags full of gifts, I was hauling my life away from Brooklyn in a rental truck.

Good-bye, New York.

Slow and steady, careful not to take sharp turns, I made my way out of the city. Past the brownstones in my neighborhood and the concrete, glass, and steel downtown. Past the stone barns and Victorian farmhouses in Pennsylvania. Up and down the stark hills of West Virginia.

When I finally hit I-70 at the Ohio border in the ink-black night, I pulled off at a truck stop, just to rest my eyes, and ended up sleeping for a few fitful hours.

When I woke up, groggy and stiff, the light was gray again.

I filled the gas tank and poured bad truck-stop coffee, the kind that was so weak that

someone could have just murmured “coffee” over a cup of hot water and it would have tasted the same. But it was better than nothing.

At the next Starbucks in St. Clairsville, I got a triple-shot latte and one of their cinnamon scones. Even the jolt of coffee and spice couldn’t nudge my taste meter off “Dull.” I guess I had to accept that for now.

Driving through the rolling farmland of central Ohio, I let my mind wander as I kept my eyes on the road.

It wasn’t often that I had difficulty tasting something. Flavor was the way people like me made sense of the world.

We knew that there was a flavor that explained you—even to yourself. A flavor whose truth you recognized when you tasted it. A flavor that answered the question you didn’t know you had.

Perhaps it was a voluptuous vanilla that your sharp-edged self could sink into like a pillow. Or a homesick pomegranate, each seed like a ruby slipper that would take you back to the place where you were loved and where people had missed you.

That’s where I was going. If only I could taste it.

By the time I reached Columbus and headed south on I-71, I knew I was only two hours from home.

Unlike other aging factory towns around it, Millcreek Valley was reinventing itself as a bridal district. Now in the small 1840s brick cottages, two-story Italianate storefronts, shotgun-style houses, and smattering of nondescript sixties modern brick-and-chrome buildings, you could find lingerie, bridal gown, tuxedo, and honeymoon travel shops. Wedding planners like my high school friend Roshonda Taylor had customers who traveled from three states away. The old brick five-and-dime had become an upscale boutique, selling Vera Wang and Monique Lhuillier gowns.

And that was why I was opening my bakery there. Well, one of the reasons. I wanted a destination place with a ready-made market.

In the bridal business, everyone knew that December was the biggest month for engagements. In January, those happy brides-to-be would start planning their weddings, so we had to be open by the first Saturday, when hordes of mothers and daughters would crowd the sidewalks, shivering from shop to shop.

And the second reason? I needed a project. A big project.

Anything to help me forget I had nowhere else to go and nothing else to do.

When I finally pulled up to the stoplight on Millcreek Valley Road, ready to turn down Benson Street, I gave myself a long, hard stare in the rearview mirror.

I had inherited my father’s dark auburn hair along with his green eyes. But I also got my mother’s unruly curl, so my hair had a tendency to escape a topknot or ponytail every chance it got. Today was no exception.

I was only thirty-two, but I thought I looked older. Much older. Sleeping in a truck stop in the middle of nowhere on a cold night will do that to you. I pinched my cheeks for color and put on a quick swath of lipstick. I was no primper, but there was something really depressing about looking as drab as you felt. As my aunt Helen often said, “Fake it till you make it.”

That was the corollary to Millcreek Valley’s unwritten rule: Work hard and don’t complain. People here put a premium on niceness and disapproved of moaning and groaning. Especially on Sunday.

As I pulled into the parking lot of my soon-to-be bakery, right next to my soon-to-be house, I saw Roshonda across the street, opening the front door of Jump the Broom. I waved at her, thankful that my good friend was now my business neighbor, then jumped out of the truck.

We met in the middle of Benson Street in a big hug, then walked arm in arm back to the parking lot.

“Well, you still look like the same Claire O’Neil I knew in high school, thank goodness. I’m so glad you didn’t go all big-city glam on me. I really missed you, sweetie,” she said, holding on tight. “And now that you’re back for good, we can remind the people in this one-horse town how sophisticated thinkers have fun.”

“Yes, of course.” I nodded with mock solemnity. “Like the time we wrapped ourselves in Christmas tree lights, plugged ourselves in, and danced in front of my house?”

“People still keep asking me, ‘When is the next Festival of the Dancing Lights?’”

“Or when we bribed the opposing women’s softball team with coffee-toffee bars?”

“Strike out, fly out, just get yourself out; then you get a cookie. That was the deal.”

“I’m surprised we didn’t get kicked out.”

“We saved that for later. We can get ourselves kicked out of lots of places now.”

We both laughed and knew that wasn’t about to happen. We talked a good game, but we were both Goody Two-shoes at heart. When other people in your family chose to be bad, somebody else had to be good. That didn’t mean we didn’t have a yen for bad boys who always messed us around. You’d think Goody Two-shoes would be smarter than that, but then they’d have to call us Smarty Two-shoes, and have you ever heard of one? No.

“I got you a welcome-home gift,” Roshonda said. “It was too heavy to carry, so I had them put it on your front porch.”

We walked past the bakery to Gran’s old house, the one that I was fixing up for myself since Gran now lived in Mount Saint Mary’s memory care wing. A fresh coat of dark gray paint and cream trim had the shotgun-style house looking pretty good. I spotted Roshonda’s gift on the wide front porch, right by the black front door—one of the concrete geese that everyone around here wanted as yard art so they could dress them up in outfits for almost any occasion or season. This one wore a chef’s hat and a baker’s apron. There was a gaggle of concrete geese in the parking lot of Hodapp Hardware on Millcreek Valley Road keeping watch over the town, but none of them ever laid that golden egg as far as I could tell.

Maybe mine would be different. I checked underneath.

“Bad news. No egg,” I told Roshonda.

She looked, too. “Good news. No goose poop.”

I unlocked the front door. Roshonda and I went inside the house, which was just waiting to be filled with all the stuff I had in my truck.

We walked from the front parlor to the dining room and back to the kitchen, then upstairs to see the two bedrooms and home office on the second floor. The new bed and upholstered headboard that I had ordered online were already set up in the largest bedroom.

“It’s beautiful. Fresh and quiet and calm. It feels good in this house,” Roshonda said.

“I can’t wait to move in. Gavin did a great job.” Our high school friend Gavin Nichols had begun his career in the art department of a large advertising agency in Chicago and then quickly charmed his way into a coveted in-house marketing vice presidency at Quaker. But after spending some time climbing the executive tree in brand management, Gavin began to feel hamstrung by corporate life. A couple of years ago, he announced to us he was chucking everything to start his own space planning and interior design business back in Millcreek Valley. Oatmeal’s loss was my gain. Of course, the rumor was that Gavin had also left a serious relationship. Still, we knew not to pry; he’d tell us if he wanted us to know.

When I called Gavin to tell him I was closing things up in New York, he shouldered the massive renovation of Gran’s house without missing a beat. And he was also helping me revamp the Rainbow Cake building. I couldn’t wait to see that, either.

“Let’s bring in a few things, just to get you started.”

Roshonda helped me unload the handcart from the back of the truck and wheel a few boxes into the kitchen. She also wheeled in my two suitcases.

“When are the guys coming to move you in?”

“Not for another two hours.”

“Well, then let’s take a look at the bakery, shall we?”

Although Gavin had texted me photos as the work had progressed, it still wasn’t like seeing it in person. I hoped it looked as great as my house.

The simple truth was that I owed Gavin, big-time. While my New York life was melting down as fast as buttercream frosting on a ho

t day, he took charge of my escape plan, which included renovating the vacant old library building for me.

I found the front door key in my purse, and we stepped inside the revamped storefront.

When I turned the lights on, I felt like I had stepped inside a Tiffany box.

“Oh, Neely!” Roshonda said.

The walls were painted a robin’s-egg blue. Antique wood-and-glass display cases had mottled milk chocolate–brown marble countertops. Antique iron-and-glass stands would make the future little cakes (under their glass domes) pop up and down on the counter like jaunty hats.

From the top of the left wall of the bakery, Gavin had hung a canvas curtain and arranged a display area in front of it. Both the curtain and display would change each month—as would, of course, the colors and flavors we showcased. The idea was to sell not only cakes, but also cake stands, serving pieces, plates, paper napkins, and other goodies, so once your little cakes got home, they’d look as good as they did in my bakery. One-stop shopping.

On the right, Gavin had arranged a seating area with dark bentwood chairs and café tables. It looked like a tea salon in Paris.

I sighed with delight.

But I wanted to see where I would spend most of my time.

The work and storage areas were screened off in the back, although I would have been happy to show off my two Vulcan convection-ovens-on-wheels and the big stainless steel worktable with the cool marble slab at one end for chocolate work.

The calm milk-chocolate plaster walls, stainless steel, and white marble made the workspace look like a shrine to the cake baker’s art. And I liked to think it was.

“Does this start to make up for everything else?” Leave it to Roshonda to get right to the point.

I nodded yes. I was too tired, too frazzled, to cry.

She offered to help me put things away, but I knew she was busy, too. And I wanted to get into this new life without distraction.

“I’ll leave you to it, then,” she said. “Just text me if you need anything.”

The Cake Therapist

The Cake Therapist