- Home

- Judith Fertig

The Cake Therapist Page 13

The Cake Therapist Read online

Page 13

Edie had her mother’s pale coloring and lithe figure, her creativity with the needle, her love of reading. But none of this paid the bulk of the bills. It was Olive who had Mama’s blunt practicality. And Olive who worked two jobs—days at Oster’s and some nights at Hinky’s waiting tables. If Olive didn’t sass the customers, she made good tips. But that was rare.

“Why do they think they can pull that crap with me?” Olive usually complained when she got home late, slamming the door for good effect. “I tell those bozos I’ll pour the next beer in their laps.”

The attack that miserable night could never have happened to Olive.

Sometimes, Edie wondered whether it really did happen at all. But even Edie couldn’t imagine it away.

She had been so close to home.

Since that night, she relived the attack when she fell asleep, exhausted, long after Olive had drifted off. But the man didn’t wait for the dark before he frightened her anymore. She had only to shut her eyes and he appeared again in her mind. Tall. Faceless. Smelling of whiskey and creek water. Cruel. Coming out of nowhere.

Every day had become a waking nightmare. Edie startled at every sudden noise, every shadow.

She had been walking home so happy to have the money from Mrs. Ellison. The money more than made up for how long she’d had to stay at their house, how late she would get home. She remembered crossing the street from the café and walking under the aureole of lamplight, dim in the fog.

He had gotten a good look at her. He had chosen her. He could choose her again. It was only a matter of time before he saw her and followed her home.

But when Edie tried to visualize him, she couldn’t. He had been hidden in the shadows, and it had all happened so fast. Edie didn’t want to remember the attack, but she had flashbacks more and more often. . . . After these incidents, she combed her memory for a detail that might reveal something. She knew how tall he was, a head taller than her. He was strong. She could still smell the stink of him. She heard the rasp of his zipper, the grunting noise he made. But she didn’t remember what he looked like. The color of his hair or his eyes, the shape of his face. Whether he was slender or stocky. She didn’t know.

And that terrified her. He could be almost any man.

Every night, Edie startled awake, her heart pounding so loudly she thought it would surely wake Olive. Her mind played back that night like a black-and-white newsreel, with the same story over and over and over again. And each time, Edie thought she had to pay even closer attention. Maybe this time, she could slow it down. Maybe she would really see him.

Edie didn’t have much to tell anybody. Olive would want facts, and Edie had very few.

Olive would be mad—and ashamed of her. Olive would say it was all Edie’s fault for being so stupid, for not accepting a ride home from Mr. Ellison. For always having her head in the clouds and not paying attention. Olive would tell her to stop being a baby. To stop being scared.

“You don’t look right, Edie,” Olive kept saying after the night they found the red shoe on their front stoop. “You’ve got big circles under your eyes, and you’re throwing up all the time. You should go see Doc Cunningham. You could have a stomach ulcer. There’s a guy at Hinky’s who says he has one, but he still gulps down that boilermaker every night when he gets off work. And then he doubles over, acts like he’s dying. Stupid.” Olive shook her head.

But they could afford Doc Cunningham just as much as they could afford a full load of coal. Edie shivered again.

She quickly folded the dimity she had fashioned into a nightgown and placed it in the bottom of the needlepoint sewing bag she would use for a suitcase. Her mother’s wedding ring, wrapped in a twist of a fine lawn handkerchief, was safe in the side pocket that snapped closed. She didn’t really want to take the ring. It belonged to her and Olive both. But she didn’t have much money in the red coin purse. She should have thought of that when she paid the milkman yesterday. Olive would be okay. Olive always was.

Edie knew she had to go where he couldn’t find her. One day, maybe, she could come back. One day.

One day when she remembered. Or was stronger. One day after she had slept and dreamed undisturbed. One day when she felt better.

In the kitchen, Edie stacked the dishes from the draining board on the open shelves. She swept the worn green linoleum floor. She folded and hung the embroidered towel on the handle of the gas oven.

In the middle room, she paused, memorizing the details: the tailor’s dummy, the long coatrack hung with finished garments clothespinned to hangers, and the small plum-colored armchair where her father used to sit before he got sick.

That reminded her. She picked up her favorite childhood book from the little table and slipped it into her bag. The childish penciled handwriting of the girl who owned it first—Caroline Edwards—was barely legible on the yellowed front page. Olive would never miss it because she never read, if she could help it.

Maybe, like Princess Irene, Edie would someday follow the magic thread to the top of the castle and escape the goblin below.

The clock ticked each second in the silent house.

If she waited any longer, she would have to run.

Reluctantly, she changed into a dress. But it was too cold for the dress, so she put on the old cardigan, then her spring coat, and buttoned it up. It still hung loosely, even with the extra bulk. She pinned the hat with its pastel flowers to the back of her head. It was too cold for a spring coat and too late in the year for pink flowers. But her winter coat was gone.

How the man had hurt her, how she ruined her coat, how she ruined her life—it all threatened to play again. He had hurt her so bad that Edie had not had her period yet. Nobody talked about things like that, and Edie was too timid to ask. Maybe she could see a doctor somewhere else.

Edie locked the front door behind her, started to run, and almost slipped on the stone slab sidewalk in the freezing drizzle. She slowed down, careful on the wet pavement, almost skating in her shoes to Market Street, then turned for the station, looking wildly around her. She didn’t see the man, but he could jump out from anywhere like he did before.

She waved her arm at the ragman’s son, parked with the horse and cart at the side of the brick-paved street, taking meager shelter under the few dried leaves still left on a big sycamore.

Edie climbed into the cart next to Shemuel, and the horse began to make its way down Market Street to the train station.

Shemuel’s plan was to sell the horse and cart to Mr. Steingarten. Edie stepped down from the rig and stood outside at the ticket counter. She could see over to the Steingartens’ house right on the railroad tracks, a short walk from the station. Shemuel walked toward the old carriage barn in the back, waving his arms at the stout woman in her blue housedress and sturdy shoes. A gust of cold wind blew the woman’s skirt and Edie saw her stockings secured in knots above fat knees.

“Young man,” she heard Mrs. Steingarten reprimand. “You can’t leave that horse and cart here. You’ll have to come back later. Mr. Steingarten isn’t home yet.”

But Shemuel kept arguing with her.

It was no use. Edie knew from dealing with her Fairview ladies that Shemuel would not be paid today. He wouldn’t be paid at all because he wouldn’t be back.

Something else to go wrong.

She’d have to buy his ticket, too.

She reached in her purse.

“How much is two tickets for as far as this train goes?”

“Well, miss, this train goes all the way to Chattanooga with one stop at Queen City Terminal.”

Edie remembered the last movie she and Olive went to see together at the Vogue. Sun Valley Serenade, with the Glenn Miller Orchestra playing “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” That was all she knew of Chattanooga.

“Miss. Miss! One-way or round trip?” the ticket master asked impatiently, peering at he

r through his wire spectacles.

“One-way.”

“Pullman berth for overnight? That’s two-fifty extra. Each.”

“No, just the tickets.”

He squinted, licked his pencil, and did the math. “That will be sixteen dollars and twenty-four cents.”

Edie reached into her purse. Her hands were so cold, they didn’t seem to work. She pawed out the small roll of bills from the inside pocket of her bag. She should have remembered gloves.

She looked down the tracks. Mrs. Steingarten was pointing a shaming finger at Shemuel as he stomped around in her front yard.

The ticket master rolled his eyes as he separated and smoothed out each folded bill before giving her the change. “You should go inside where it’s warmer,” he chastised.

She blew on her reddened hands, but it helped for only a moment. She put the two tickets in the pocket of her bag.

Inside, she sat on a worn bench by the potbelly stove.

Edie closed her eyes, tried to relax her tense shoulders, willing it all away. She shook her head as if to loosen and turn the page stuck in her own story.

She kept her eye on the only door, through which that man could walk at any moment. The small room started to close in on her.

She got up, suddenly, and ran outside onto the wooden platform. She felt the snow beginning to fall in heavy white tufts. Edie turned her face up to the sky and let the gentle snow drift, whisper-soft, on her skin. She fought the urge to run home, get under the covers, and never leave her bed again.

She noticed the quiet, as if the whole world had stopped spinning and was still for a moment. Maybe Shemuel and Mrs. Steingarten had reached some agreement.

Tufts of falling snow covered everything—the tracks, the scrubby trees up the hill on the other side, the rooftops—like a thick chenille bedspread.

But something was coming.

Edie saw the rumbling dark shape of the approaching train plowing through the snow. Its shrill whistle made her jump.

And there was Shemuel still stomping around Mrs. Steingarten’s yard, insisting on being paid.

“I’ll call the police if you don’t leave this minute,” Mrs. Steingarten shouted.

But Shemuel was caught up in his own rage.

He won’t make it.

Edie walked back to the ticket master. “Can I have an envelope, please?”

Rolling his eyes, he passed her a large, much-used manila envelope. “This is the only one we have. Will this do, miss?” Edie didn’t catch his snide tone.

The train pulled to a stop.

With numb hands, and looking worriedly down the tracks to the Steingarten house, she put the ticket into the envelope. “This is for Shemuel Weiss. He’ll be here in a moment.”

On shaky legs and with hands that didn’t seem to work, Edie wrapped an arm around the frozen iron railing and pulled herself up the steps of the last passenger car. She would be able to see him from there.

“The ragman’s son?” the ticket master called after her. Edie heard the scorn in his tone. “Are you sure about that?”

Edie nodded yes through the train window.

She sank into the last seat. The conductor, trying to keep warm in a woolen scarf and fingerless gloves, punched her ticket. Holding on to each seat, he stiffly made his way to the front of the car, then opened and slammed the door behind him as he walked forward across the coupling to the next car. Edie felt the rush of cold air and again wondered whether she was doing the right thing.

And where was Shemuel? Could she do this by herself?

She couldn’t see out. The windows started to fog up. It was eerily quiet, the snow muffling all sound. Edie felt cut off once again, so close to home, yet so alone in a place where danger could come out of nowhere. Something was about to happen; Edie just knew it.

What would Olive do? Well, for one thing, Olive wouldn’t run away. Olive would stick to the facts. She would take stock.

Edie tried to calm herself by turning her bag out onto the seat and bending over to look more closely at everything she had packed. One item at a time, she tallied the two changes of undergarments, dimity nightdress, half-used jar of cold cream, comb, sweater, the old storybook, some rolled bills and loose change in her coin purse. The ring in a twist of handkerchief. Quickly, she did it all again. And again.

Why wasn’t Shemuel there yet?

She looked to the front of the car and saw a man’s silhouette through the grimy, fogged-up door window. It was not the short, squat conductor, but someone else. Someone tall. His profile was somehow familiar to her, and Edie gasped, her eyes wide. He turned the metal handle on the door, but it was stuck. He banged on the window, tried the handle again.

The train whistled its departure. She had only a few seconds.

She stuffed her things back into her bag and stumbled down the aisle. The door to the caboose was not locked. She let herself in, slamming the door shut behind her. She raced through the car to the very end of the train with just enough time to jump out the back as the locomotive lurched forward. She went down hard on the gravel between the tracks, but picked herself up and started to run.

The snow was coming down so hard that she could barely see a foot in front of her. She crossed to the other side of the tracks, like a ghost drifting through a dream.

She steadied herself and looked up as a vee of wild geese flying low in the heavy air pointed the way forward, up the convent hill.

Edie wove through the brush after them, toward flickering colors she could just make out—blue, then rose, then gold. She almost tripped over a downed sapling, but finally reached the circular brick driveway. She veered to the left, toward the light.

Edie’s footprints disappeared in the snow almost as fast as she made them.

As she got closer, she saw that the glimmering lights came from an arched stained glass window.

Edie felt around the rough stone walls until she found the door.

In the dim interior, Edie recognized the statue of Bernadette kneeling below Our Lady of Lourdes set in a high stone alcove. Light haloed from votive candles in each deep windowsill.

Edie could see her breath. She put her carpetbag down and sat beside it on the thin padding of the long kneeler. She pulled her knees up and gathered her coat around her, trying to bury her numb hands in its folds. Maybe if she just rested a little bit . . .

There was a stillness and a quiet that came from more than the snow. Her thoughts slowed down. Her breathing became deeper, calmer. For the first time in a long time, Edie felt that maybe here she could be safe for a while. She leaned her head against the side of the kneeler, exhausted.

When Edie woke up, it was dark outside. One of the votives had gone out, but she was warmer.

More light, more warmth, her instincts told her. She took a long match from a cup and lit a pillar candle on the tiered iron stand next to her.

As the flame burst into yellow light, pulsing off the plaster walls, she saw her father, coming home from the cotton mill, twirling her mother around, and giving her a kiss. Olive clapped her hands and laughed. A young Edie looked up from her book. And then the image was gone.

Edie touched another match to a candle, and this time, the expanding light turned golden. In her pale blue housedress and the yellow checked apron, Edie’s mother rolled out pie dough in the warm kitchen, laughing at her daughters’ blackberry fingers as they showed them to her—still stained, even after washing with Castile soap. Olive stole a scrap of pastry when her mother wasn’t looking and ran off, daring Edie to catch her. But this faded, too, as the match flickered out.

Edie struck a third time and, going from flame to flame, lit every candle.

The little grotto filled with brilliant white light. The faint scent of rose blossomed in the warming air. The robin’s-egg blue of Bernadette’s gown and Our Lady’s cloa

k began to shimmer. The walls receded as the light expanded and pushed them back.

On Edie’s upturned face, the dark shadows of torment vanished in the glow. She felt young again, innocent. She brimmed with yearning and hope. She knew this story.

She knew this story.

But this was real life . . . and this wonderful moment would disappear like the others. She dropped the match and fell to her knees. She put her hands together in prayer.

She whispered: “I can’t go back. I can’t go on. I don’t know what to do.”

She begged: “Please help me.”

She murmured this litany, over and over and over again.

I can’t go back. I can’t go on. I don’t know what to do.

Please help me.

When the Lady finally came in her black gown with the big white collar, her face shining in the warm light like a full moon, she gathered Edie in her ample arms as if she were a baby.

Her voice, so loving and gentle. “My child, my child . . .” She rocked Edie to her. Edie smiled and closed her eyes, sinking into the embrace.

And Edie, blissfully, forgot.

9

MARCH

Lemon and Blueberry

By the time the Professor arrived, I had already been supercharged with my second double-shot latte. I stirred in the extra sugar before foaming the milk. The heart-shaped design I was going for morphed into what looked like a goose. I hoped that was not some premonition of the day ahead.

“Good morning, ladies.”

“Well, it’s official, Professor. Your good taste has been our inspiration for March.” I gestured toward the blueberry-colored curtain that allowed the little lemon goodies on the display table to pop out in contrast. Since we’d opened in January, his default setting for a breakfast cupcake had been blueberry and lemon.

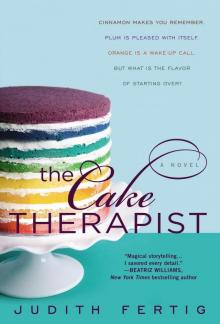

The Cake Therapist

The Cake Therapist